I was searching for old photos of an area in my neighborhood around Ohio Avenue between Victor and Sidney Streets. As I was searching through the online Missouri Historical Society (MHS) collection, I found a photo that struck me:

What a gorgeous building. It almost looks like a massive Arts and Crafts-style house, but per the Missouri Historical Society photo description, it was a factory:

“Horizontal, black and white photograph showing an exterior view of the Hammer Dry Plate Company building at 2527 Ohio Avenue. The two-story brick building extends for an entire block and has large windows and timbering under the eaves, which gives it the appearance of a more residential building. A smokestack is visible in the background of the photograph behind the building. A shadow of the photographer is visible in the bottom-center of the photograph.”

The photo, dated December 4, 1934, was taken by one of the best photographers of St. Louis streetscapes: Isaac Sievers.

Two mysteries had to be solved. One, where was this building? Two, what was the Hammer Dry Plate Company?

I will do a separate post on the history of Hammer Dry Plates, founder Ludwig Hammer, and his son Ludwig Jr.; here, I’ll focus on the factory.

Google shows the 2527 Ohio Avenue address listed in the MHS website just south of Fox Park (the park).

I was highly skeptical, as that is the former Fox Brothers Manufacturing property, now Rung for Women.

Further, Geo St. Louis doesn’t list the Ohio address as active. The recorded photograph address must be incorrect on the MHS website.

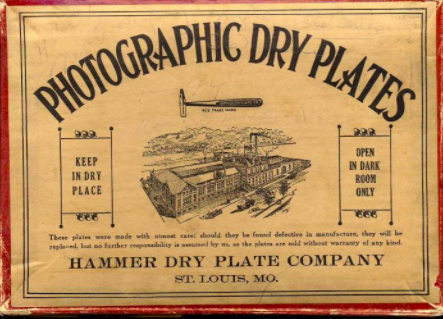

A search of Hammer Dry Plate Co. produced a dry plate box with a view of the factory and a location at Ohio Avenue and Miami Street on an advertisement:

See the factory on the dry plate box? It ran nearly the full length of the block, seemingly along the south east side of the block.

Let’s take a look at the current intersection of Ohio and Miami in the Gravois Park neighborhood:

That had to be it, right across the street from South City Hospital (formerly St. Alexius). My guess is the former Hammer Dry Plating factory faced the Ohio Avenue side toward Miami Street.

Sadly, the gorgeous factory in the Sievers picture is long gone.

Here’s what you see from Miami Street today, a gorgeous Art Deco building in its own right.

2711 Miami Street

I had to learn of the factory’s demise.

A couple more clicks reveal the current Art Deco building on the property was owned by National Graphics. Per the St. Louis Business Journal, they transitioned from a photography business to ink jet printing.

“Founded by W.R. “Bob” Gould and two partners in 1974, National Graphics was a manufacturer of photographic materials until Bob Gould saw the future was in the computer field.

Today, National Graphics produces a line of ink jet media (paper) at its plant in south St. Louis and has established a subsidiary, IJ Technologies, which handles the sales and marketing of the products.”

So, there is a history of photography here…another clue…maybe the current proprietors know the history. When I found out IJ Technologies is still in operation, I got on the horn for the cold call.

A warm voice picked up on the other end of the line: president Liz Gould. I introduced myself, trying to be extra cordial as not to make her mad and hang up from a non-business call.

Quite the opposite, Liz knew all about the history and connection to Hammer Dry Plating and dove right into the conversation. I could tell she was good folk and had an interest in history. We spoke for ~15 minutes and she said I really needed to talk to one of her employees, Mark Boswell, who has some great information on the property’s history. She also indicated she has some relics from the Hammer days.

She invited me for a visit. A few days later, I met with Liz and Mark at the factory.

During our initial conversation, Liz gave me a nugget of information I needed: a fire destroyed the original factory on the property; but, some of it remains to this day.

That is the clue I needed to unravel the mystery. To the Central Library I must go!

I wanted to learn more about the Hammer Dry Plating Company and determine when the fire destroyed this beautiful factory at 2701 Miami Street?

My wife, an impressive sleuth, took on the history of the Hammer family, I focused on the building.

The ace librarian on staff produced the documentation we needed in less than ten minutes. He handed us a manilla envelope filled with news clippings from the St. Louis Post-Dispatch…this means we’re not the first to research this company. There’s already a file!

Shannon got some information on the Hammer family and business, which I’ll share in a separate post.

I got a clue that pointed me to the factory fire.

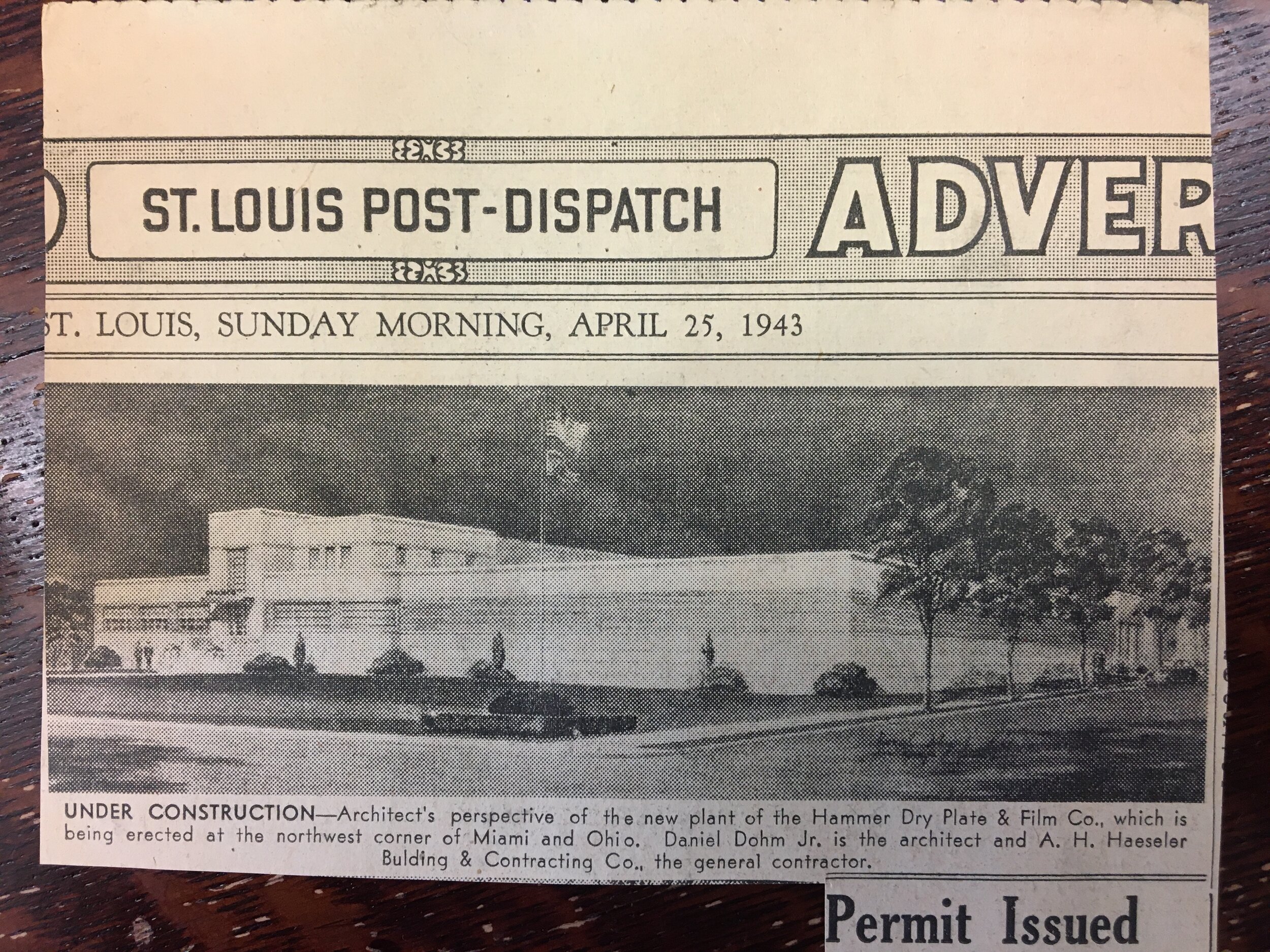

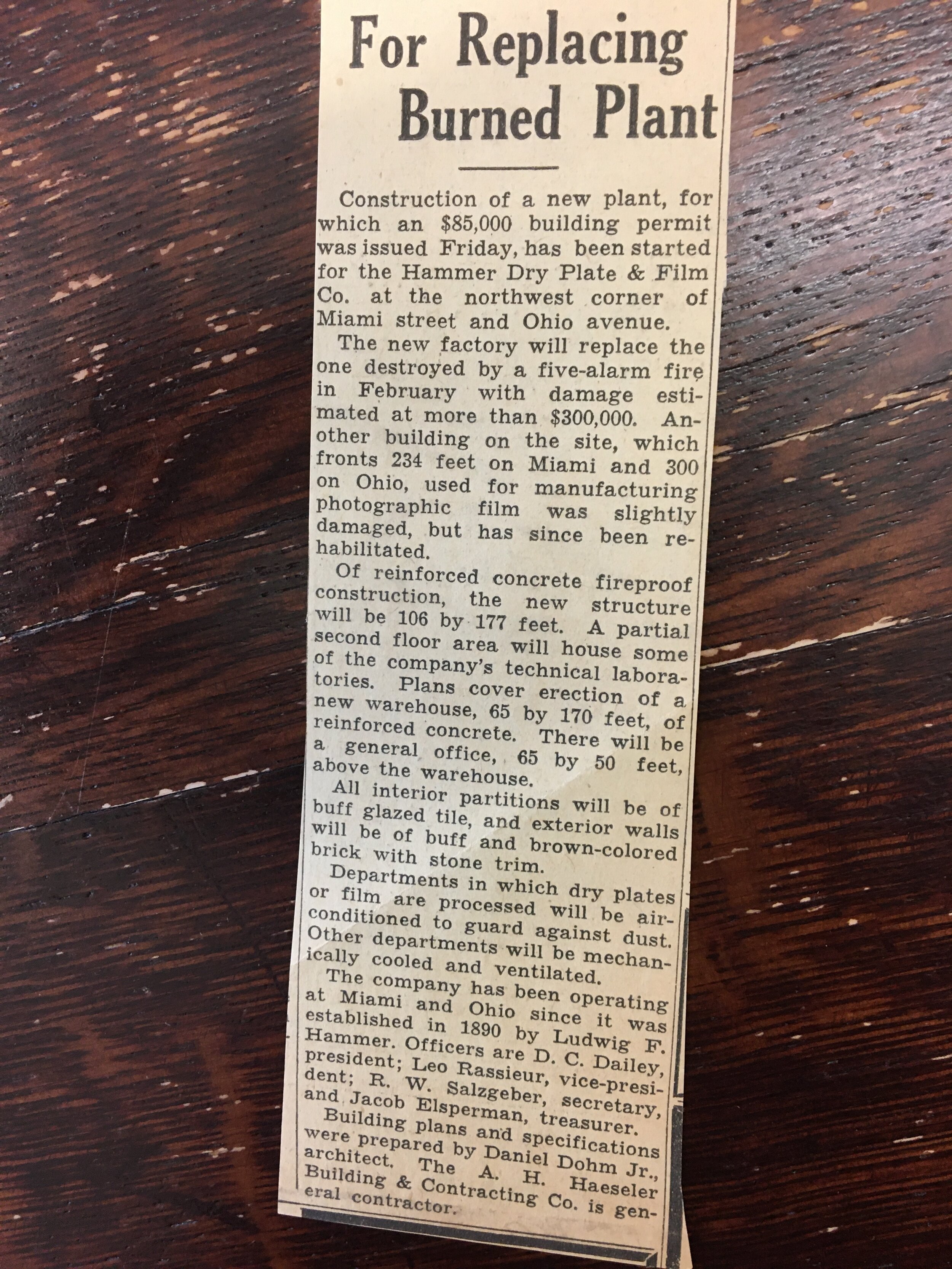

From an April 25, 1943 Post-Dispatch article on the building that would replace the former Hammer Dry Plating factory, the fire was in February, 1943.

The new building was actually built toward the south east section of the lot. And the grade was higher, as the final structure sits atop an elevated hill.

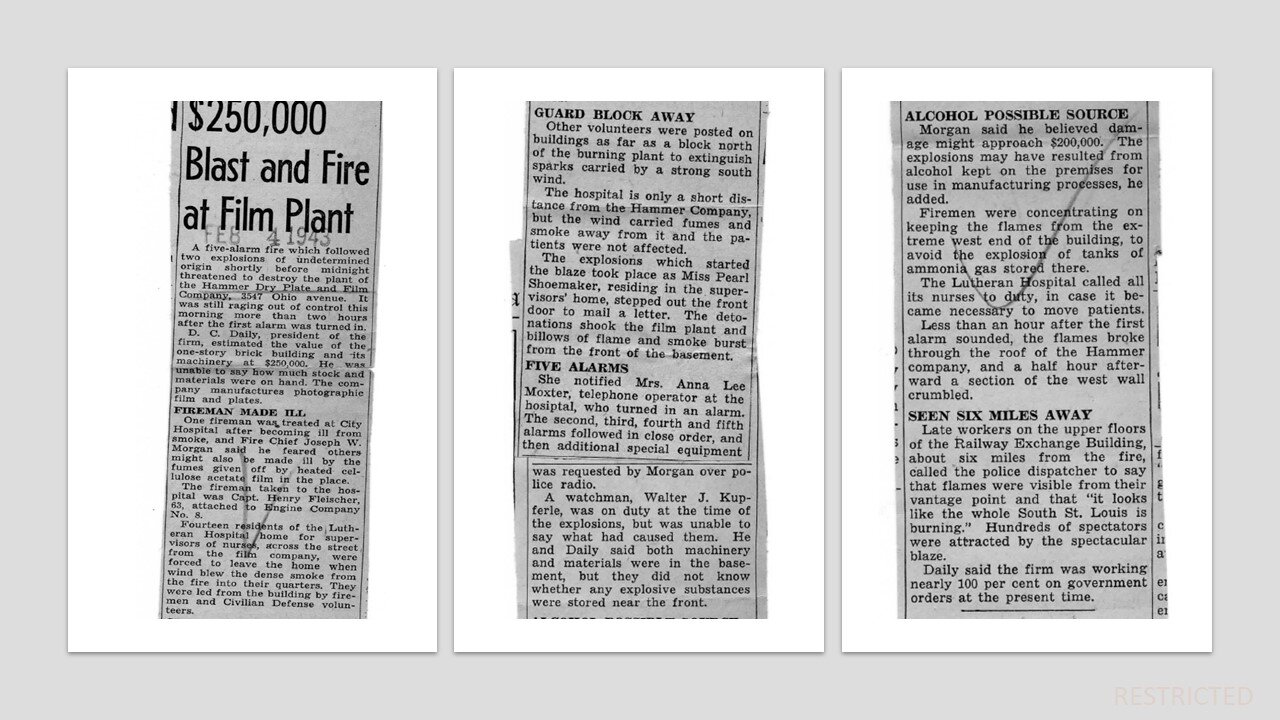

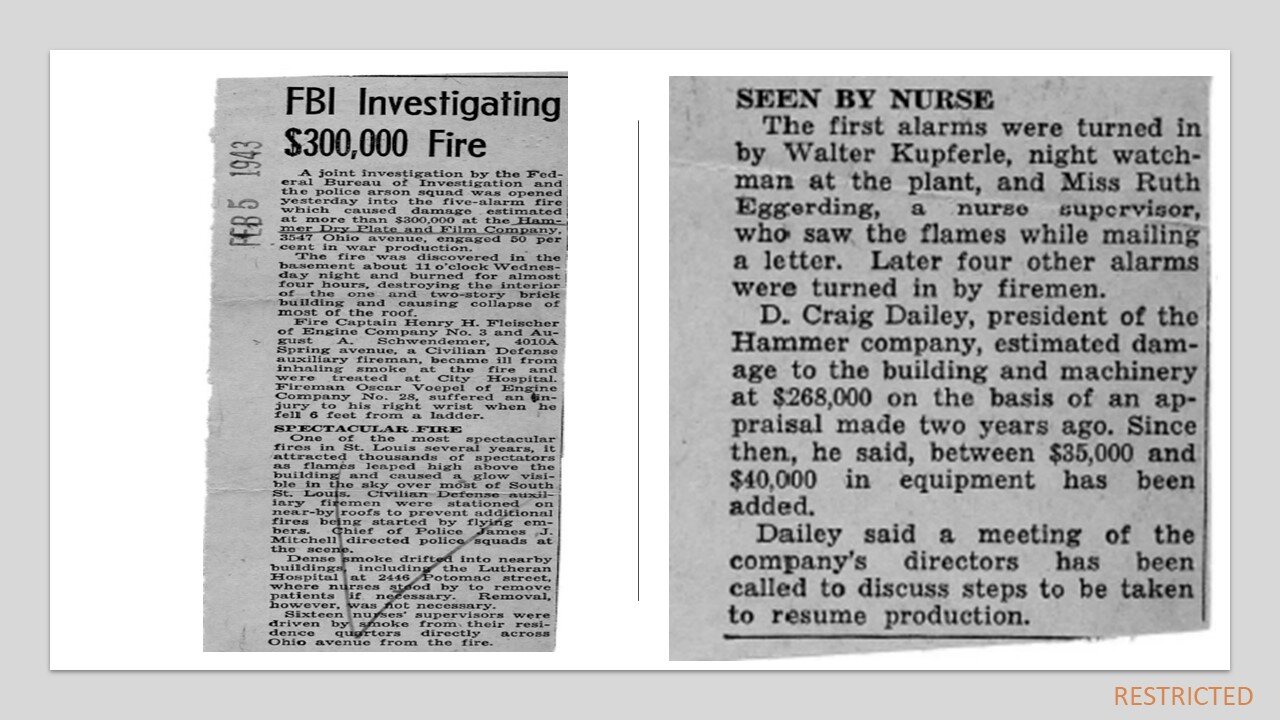

Now, I had to get the microfilm to see if there was a report of the fire. But, due to COVID precautions, SLPL are only allowing one person in the microfilm area at I time, so I couldn’t get in. I sent an email to a librarian at the St. Louis Mercantile Library at the University of Missouri-St. Louis. A couple days later, the exact date and circumstances of the fire were discovered via the Globe Democrat clippings:

So the fire occurred on February 3rd and raged on to February 4th, 1943. I find it curious that Hammer was creating ~50% of its film supply for the WWII effort for the Federal Government, and they helped rebuild the fireproof building a mere two months later. The Defense Plant Corp, a war division operated from 1940-1945 to build factories to help win the war, built the factory even though Hammer retained ownership.

The fire occurred February 3, 1943, the FBI opened an investigation on the fire on February 4, 1943, then 3 weeks later, the fully realized architectural drawings, plans and building permit were issued and reported by the press on April 25, 1943. Hammer filed for bankruptcy shortly thereafter and by 1950 a Chicago investor put up $75,000 to take control of Hammer and bail them out of bankruptcy. I will dig into this a bit more in my next post on the Hammer family.

I suspect the speed at which the factory was rebuilt was due to the war, which was still raging at the time.

Thanks to the help of the librarian community, my mystery was solved.

Armed with this knowledge, I was ready for my visit with Liz Gould and Mark Bosworth at IJ Technologies.

Mark and Liz - Liz’s mother made the NG (National Graphics) artwork in the background

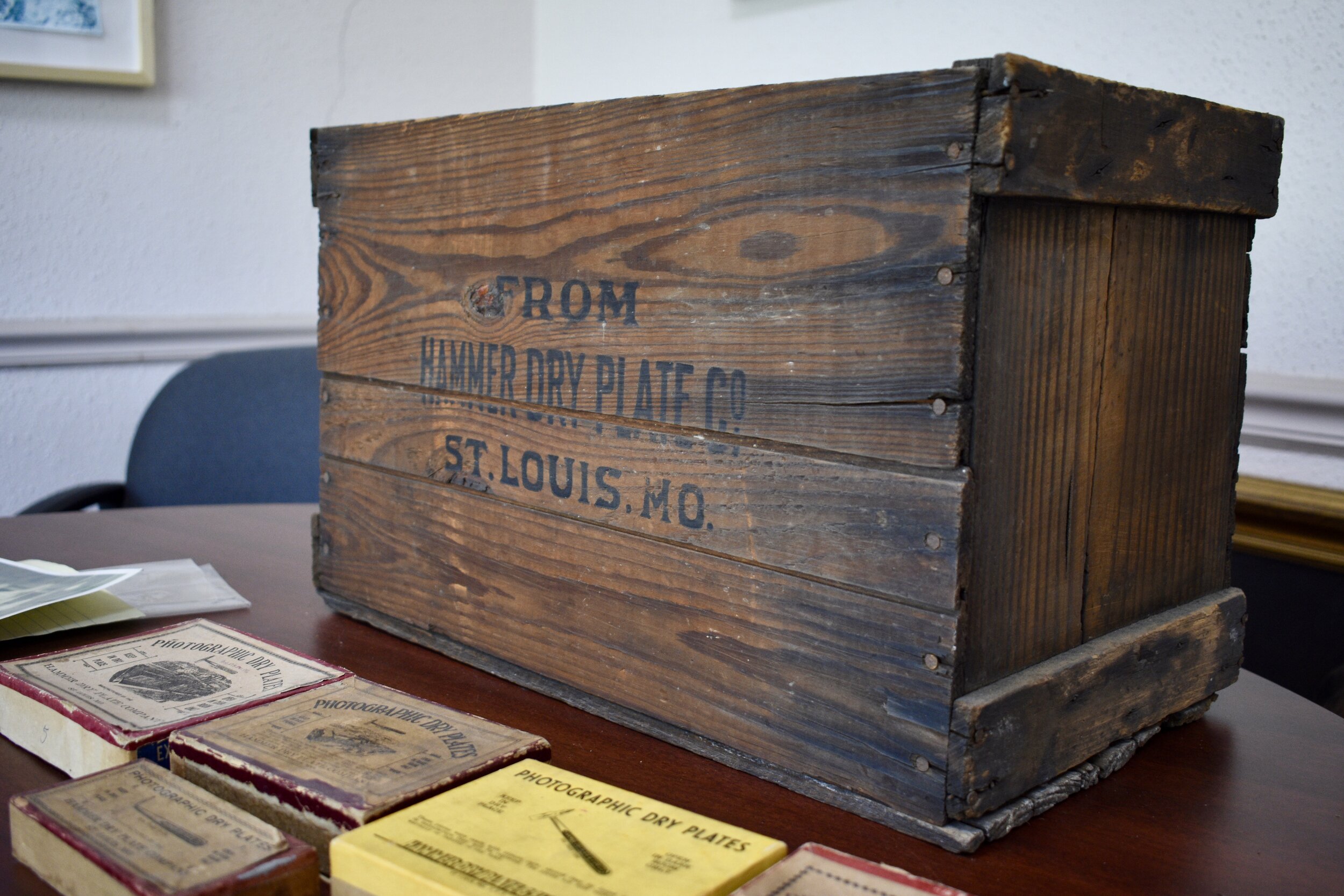

We sat down at a table with a collection of relics from the Hammer Dry Plate factory. A wooden crate and several glass plate packets, the metal hammer (great marketing “tool”), a letter opener, a matchbook cover, the “short talk on negative making” booklet that Hammer provided in every order and best of all some photos.

Hammer Dry Plating Factory - view looking north on Ohio Avenue

Hammer Dry Plate employee - Ferdinand Kolb

The photo of Mr. Kolb (1869-1949), an Austrian immigrant, was taken from the factory floor. Kolb lived at 2836 Ohio Avenue in the Benton Park West neighborhood just a few blocks north of the factory. His former home is no longer standing and the lot is owned by DeSales Community Development who are developing affordable housing in this block.

Further proof that employees used to live very close to the factories where they worked.

Kind readers, I was super excited, as I full-on entered the St. Louis history nerd zone. Be cool ice cold, don’t talk too much…get their story!

These items came from Liz’s personal collection. Liz is a native St. Louisan, running the family business. Mark is from Albany, NY. He has a photography degree, and was instrumental in curating exhibits at the International Photography Hall of Fame in the Covenant Blu/Grand Center neighborhood. Mark helped with the collection when the Hall of Fame moved from Oklahoma City, OK to St. Louis.

I was in good hands, kindred souls indeed.

Mark took me on a tour of the entire building. This Art Deco beauty was built by the government during WWII and they were not messing around. Due to the highly flammable nature of film production, they would not risk a loss of production during the war. This place would not burn again.

The 1940s “new” factory is built like a bunker. The offices, factory and warehouse sections are built of reinforced concrete and buff glazed tile.

Given that much of the film manufacturing work takes place in the dark, the hallways leading to some parts of the building are in a maze-like pattern, where you have to snake in and out to get to dark room floors. Light cannot turn corners, so this was common sense design.

Another key element of the new factory was air-conditioning. Film and dry plates had to be cooled.

Mark described that the boiler room and the central floor of the factory survived the fire and was incorporated in the new design. We walked the original wood floors and he pointed out the fans that cooled the factory spaces prior to AC. There were vents built into the floors that allowed cooler air from the basement to help with cooling. These have since been sealed due to the AC.

The reinforced concrete ceilings are vaulted, another reminder of the pride and skill the Federal Government once abided by.

Mark walked me up to the “penthouse” to envision the old section of the factory and how the deco building connected to the fire damaged section. Note the blonde and red brick connections in the photo below. They didn’t waste a brick.

Another addition to the building was made in the 1980s for more warehouse space.

Thanks so much to Liz and Mark for the time, kindness and tour…complete with a ghost story along the way.

Your shared history and good stewardship of the past and present inspire me to keep on loving St. Louis and its people.

One mystery was solved, now it was on to summarize our findings on the Hammer Dry Plate Company and the impact of the Hammer family on St. Louis photography history.