This is the first in a five-part series on gentrification within the context of modern day St. Louis.

This post will introduce the definition of gentrification and initial thoughts on its applicability and consequences in my city of almost 25 years. I will also explore whether gentrification can be measured to help cut through the subjective aspects of the concept. We’ll also take a quick look at some demographic trends in the neighborhood I’ve chosen for the backdrop for consideration of the topic.

Throughout theses posts I’ll be touching on whether gentrification is a positive, long overdue signal of new investment in a long declining city; a necessary step toward mixed race/income neighborhoods vs. uni-culture/self-segregated places. Or, is gentrification a tool of the bourgeoisie or the ham-fisted political set to introduce a more modern tool for “urban clearance” or a reset of current norms, by erasing the recent past and current set of residents in one particular spot? Are renters being displaced due to rising housing costs? Is the city complicit in marginalizing the poor and incentivizing development that only appeals to the middle or upper-middle classes?

As with most debates, there are two sides. We’ll look at both what we see as the good and the bad in Parts 2 and 3.

Before we explore these topics, let’s start with a definition. Gentrification is a relatively new word, coined in 1964 by sociologist Ruth Glass:

“noun

1. the buying and renovation of houses and stores in deteriorated urban neighborhoods by upper- or middle-income families or individuals, raising property values but often displacing low-income families and small businesses.

2. the process of conforming to an upper- or middle-class lifestyle, or of making a product, activity, etc., appealing to those with more affluent tastes: the gentrification of fashion.”

Definition #1 is easy; yes, that is happening all over St. Louis, a city that has been hit by two distinct waves of disinvestment and abandonment. But, I’m not convinced displacement is part of the St. Louis gentrification equation and we’ll get into that. The white flight of the mid to late 20th Century, and now the black flight from the late 20th Century to current day has left St. Louis with thousands of empty buildings and vacant lots. Most left for the suburbs and other regions by their own will. With this mass exodus, we lost over 500,000 residents in ~65 years. It continues per the latest Census estimates. We, as a city, have not yet hit rock bottom.

Property is cheap and plentiful, and much of it is beautiful, if not a bit torn and frayed. Some is crumbling under the elements, some is moth-balled for future reuse.

What we’re left with in current day St. Louis is a place desperately needing more people, workplaces and investment in the most basic things that will bring us back to a major, livable, mixed race, income diverse, dynamic U.S. city. The white people left in droves, now the black people are leaving too. Signs of abandonment and neglect are everywhere. Investment is finally happening in some parts, but displacement is debatable.

Definition #2 certainly seems more complicated. To me, local soul and flavor changes monthly, yearly and over longer periods. I’ve seen this happen several times in my 20+ years living in different parts of St. Louis. Sometimes culture and soul can boil down to a very small number of people and if they move, close up shop or just disappear, the neighborhood can change very quickly for better or worse. New people come in and paint their own picture and bring their own flavor over and over. It’s quite refreshing and fascinating, actually. Ever been to Little Italy in NYC? Yeah, that’s Chinatown now. People move, new people come in and make it their own. And in Manhattan, it all feels gentrified.

Discussion of gentrification gets personal and emotional quickly, if you feel like you are:

On the losing end of rising property values (a renter)

Being “white washed”

Being physically cut off from resources that are being diverted toward more affluent areas

Having your home taken from you

I am trying to be sensitive to these concerns, and hope to explore them herein. I won’t get into the academic considerations of gentrification until Part 4, but I feel it is necessary to mention one of my most returned to publications:

“They’re Not Building It for Us”: Displacement Pressure, Unwelcomeness, and Protesting Neighborhood Investment by Stephen Danley and Rasheda Weaver published in the journal Societies, 2018

Daley and Weaver are PhDs from Rutgers and Iona College, respectively. Their paper is an invaluable resource with Camden, NJ as the studied city. There are lots of parallels to St. Louis, and it’s chock full of great quotes and research. If you are like me, and trying to come to terms with criticism of development and the social impacts of economic and racial change, read this. Camden is different than St. Louis in that it’s ~40% black, 40% Hispanic/Latino and 16% white. STL is nearly 50:50 black:white with only ~3.5% Hispanic/Latino population. But, the median incomes are nearly identical and the lessons learned still shine through.

I learned that a base tenet of gentrification for those who currently live in a changing neighborhood is fear. Not necessarily fear of displacement, but fear of development that creates exclusive “white places”, making those who’ve lived in the neighborhood most recently feel unwanted or harassed for being in or near those places. That’s a heart-breaking thought. You’ve got to let that sink in and internalize it a bit to come to terms with the fact that this might be the heart of the negatives around gentrification: fear of feeling unwelcome, not displacement.

I’ve seen this in St. Louis. From law enforcement in some areas and not others, to physically cordoning off certain sections, or investing in and city responses to upper or middle class white concerns, but not concerns of those who currently live in a place.

This concern is what we can and should address and consider with every incentive handout and every street blocked with Schoemehl pots or cul-de-sacs. These physical symbols are psychologically damaging as they indicate the city’s desires to separate communities. The haves blocking out or marginalizing the have-nots.

We can work on this latter piece to embrace those already settled in a place and new residents moving to a place. We desperately need both current St. Louisans and scads of new St. Louisans if we are ever to become a healthy city with a growing population.

So when does a gentrified area become obvious? What are the signs to be seen or felt? Where can you go in St. Louis to immerse yourself in the latest round of gentrification?

Outside of the feels, is there a method to use data to define a place as gentrified?

Undoubtedly, gentrification is taking place in every aged city that’s been around long enough to see waves of generations and change. But labeling a street, neighborhood or city “gentrified” or “gentrifying” is hard to measure. There is no widely accepted method to quantify it, so it is obviously prone to subjectivity and emotion and judgement. But a feel is sometimes justified, and should not be dismissed.

So is it possible to take an emotionally charged, highly-subjective topic and use a little social science and math to try and quantify when gentrification is undoubtedly taking place? Where do we start to develop our baseline understanding of gentrification with a formula? We have no Bushwick, Brooklyn, NYC to be used as a textbook example for the study of gentrification. My daughter was studying the topic in her literature and composition class and they used Bushwick as the place of study, it is a much easier case to define the concept and term since it is so utterly obvious.

I’ve read there are three demographic indicators that, when on the rise, point to gentrification:

median home value

median household income

percentage of residents with college degrees

These metrics are likely as good as any to explore the numbers game on quantification of gentrification. So does St. Louis make the list by this measure?

“It’s a pattern as old as America itself — and it’s not going away any time soon. To illustrate, here are seven cities that have been radically altered by gentrification in the 21st century, as defined by the percentage of urban homes that went from the bottom half of home price distribution to the top half. Data was compiled by the Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland, and calculates for the period between 2000 and 2007. ”

The results from that analysis rank the most gentrified U.S. cities as: Boston, Seattle, New York, San Francisco, Washington D.C., Atlanta and Chicago.

If you layer in the college degree metric, you can add Houston, Nashville, Denver, Austin, Portland and Baltimore. These cities are attracting more college educated residents.

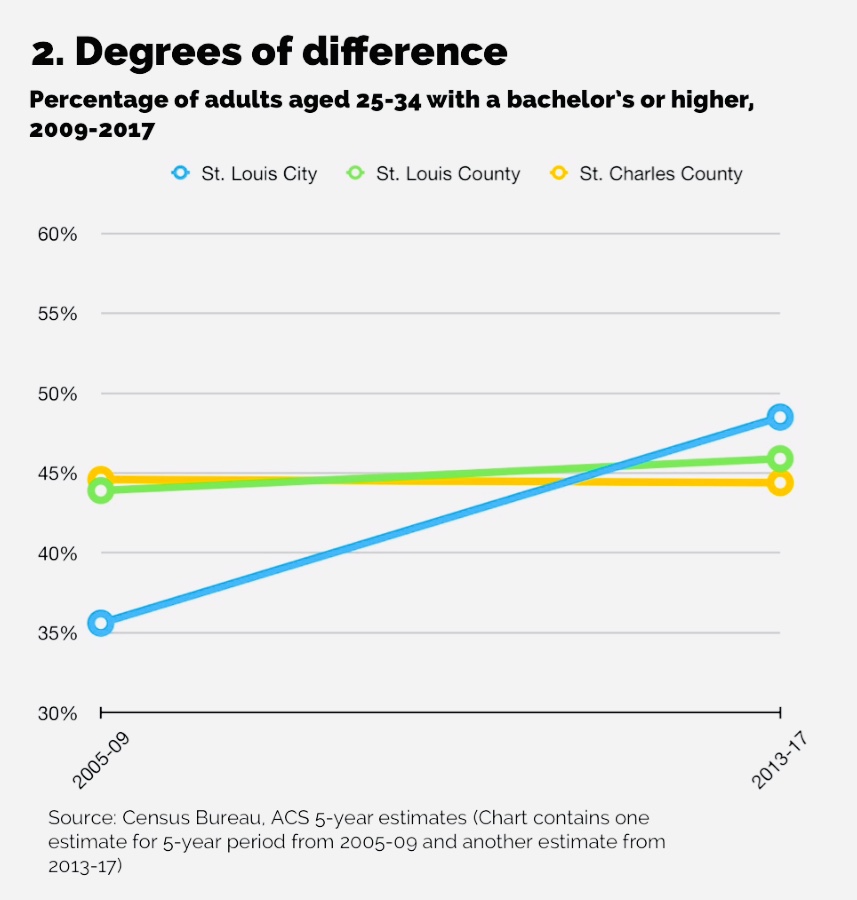

No St. Louis, but regionally, we are getting more educated compared to the aging suburbs and nearby counties to the west of St. Louis as an excellent analysis by McPherson Publishing recently pointed out:

St. Louis as a whole is not under consideration for the most obvious examples of gentrification pricing people out of a neighborhood. However, there is evidence that parts of St. Louis can make the cut on the National level if you use zip codes as your measure. Meaning, micro sections could be seeing undisputed gentrification. One such example was summarized in a 2018 RENTCafe post:

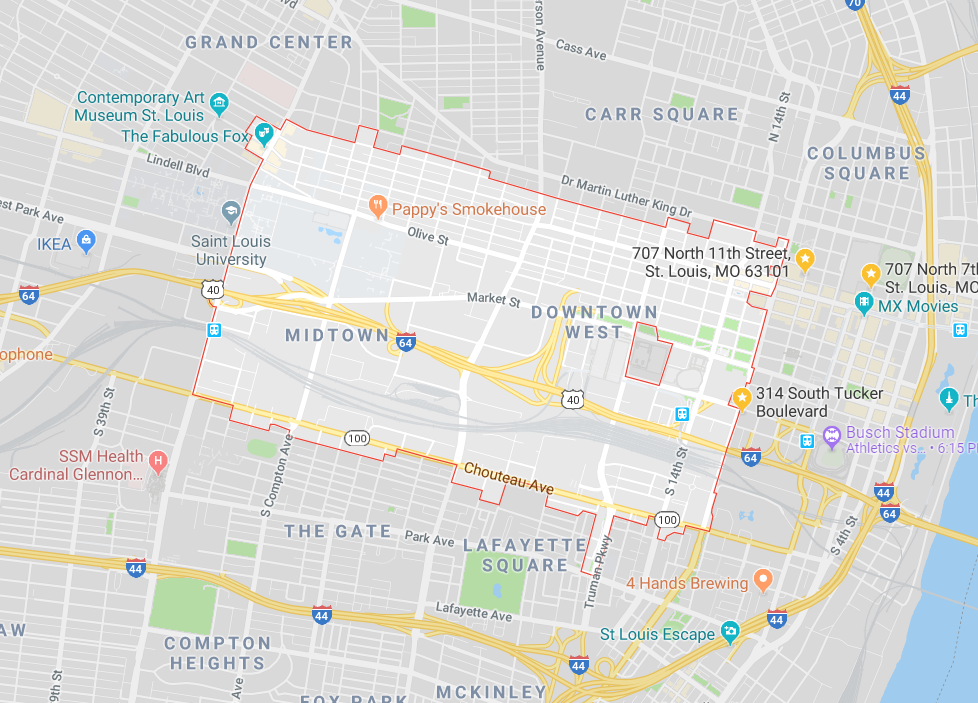

Map of 63103

So this is getting interesting, from 2000 - 2016 parts of Downtown, Downtown West and Midtown made a list.

The analysis indicated that this small section of St. Louis saw a 250% increase in home value, a 44% household income bump and 153% higher education increase. Most call that success. But was this at the expense of poor who were kicked out of Downtown and Midtown? Were people who lived there scared of exclusive white spaces and chose to leave as a result?

Well, doubtful, no one really lived in these parts to begin with, at least not in my twenty five years here. No one got displaced. Everyone was long gone already. Hell, it’s still kind of desolate, look at the map. It was more abandoned light industry, warehouses and retail converted to residential. There is a large footprint of Interstate and rail dead zones that have no housing around them. The residential places were emptied out well over 30 years ago.

Gentrification on the Delmar Divide, now that surprised me. This would not have been my go-to spot to investigate gentrification. This feels like a statistical anomaly.

Maybe I don’t know my own damn city. Is it gentrification if you go from little to no business or people to a now functioning, growing area that is attracting modern businesses and young people with college degrees? This ain’t Mill Creek Valley, Hop Alley or McRee Town…

Sure, Downtown has become noticeably younger, but I often see young black professionals or college students all over downtown these days. It feels pretty mixed and more healthy than it was in the 1990s when I moved to STL.

Which gets us back to the feel. The emotion. The subjective judgement.

I remember hearing the phrase "I know it when I see it" from a Supreme Court Justice who was deliberating over the definition of obscenity in the context of art and hard core pornography back in the 1960s.

Like pornography vs. art, I’d like to think I know gentrification when I see it. You just have to use your gut and let your experience define what is and isn’t gentrification.

I had to find a neighborhood that felt right from my gut, and Midtown and Downtown didn’t cut it. A neighborhood that might challenge one’s perspective on the positive and negative aspects of gentrification.

Awhile back, I took a fresh look at the south side of Manchester Avenue in the Forest Park Southeast Neighborhood (FPSE). It is hard to think of another neighborhood so changed in recent years. When thinking of the place in St. Louis most worthy of framing considerations of gentrification, this was my first stop. Another benefit of FPSE is people know this place, even the suburbanites know “The Grove”.

But, infill and rehabbing are not always a prime example of gentrification, especially when there is rent-controlled or lower income housing being built into the mix? The places I’ve been to on Manchester don’t feel like exclusively white spaces. Some do, but not all.

I’ve been poking around these parts for years, and while the neighborhood is getting younger, more educated and more racially diverse, it is not a slam dunk for me when trying to find the perfect example of the St. Louis brand of gentrification. It feels very mixed in housing, both big and small, old and new, expensive and not at all.

When we lost the middle class people in neighborhoods, we lost the businesses. Manchester Avenue between Kingshighway and Vandeventer was almost completely empty and abandoned in the ‘90s when I moved here. No one was pushed out by yuppies or savvy investors. It sat for years, vacant.

This is the St. Louis way. Years and years of sitting and watching a neighborhood die or rot. Then, finally, when a plan or group of investors or a non-profit is formed to try to salvage or elevate a neighborhood, then it’s called a renaissance or alternatively, gentrification.

Look at Manchester today. Gentrification for sure. But, I will argue it’s a young-leaning, racially diverse set that is using these places. Look at the patrons and employees in the bars/restaurants or the acts the Ready Room books, very diverse. I don’t see neighborhood kids being hard-assed or disrespected on the streets. I find that refreshing. I’m optimistic about that.

Few small businesses were kicked out in this example, but expensive hair salons, gay bars, affordable American and International restaurants, micro-breweries and bars catering to young people are all over now. Same can be said for Cherokee Street, I just don’t think it’s displacement or yuppie/all-white spaces being created. That’s my gut anyhow.

But, Manchester is an example of the St. Louis-style gentrification: years of disinvestment, lack of motivation and inaction. Now, there are places to go.

The cynical look at Manchester and dismiss street art, murals, trees, lights and other investments as the generation of white-only spaces, spaces for visitors and tourists, not the neighborhoods and surrounding residents. After having been in these parts for years, I just don’t see FPSE as exclusively whites-only spaces. It feels like the doors are open. They’ve been painted and fixed and the hinges are all new. But the doors appear to swing open for anyone wanting to live or hang out there.

Ask yourself which version of Manchester you prefer? 1999 or 2019.

Remember, all cities are constantly changing and in flux. Some are being developed and redesigned for the modern times. In the case of St. Louis, our city is continuing down a path of increasing abandonment and lack of investment. Vacated and increasingly unlivable in some parts, while others see massive amounts of new ideas and money, building for the future which may or may not include those that were around in the latest version of a place.

I take a historical perspective of change within St. Louis. What is now a black neighborhood or once was a Bosnian or Czech neighborhood is not staying that way for long. People move on. No one deserves claim to a place for eternity. Places changes as the people do. The current residents define the place and bring and cater to their needs and desires within a particular place. That’s what cities do. Bevo of 1980 and 2000 and 2019 are VERY different places.

Nonetheless, I needed a dead-ringer example of both good and bad examples of gentrification.

I walked away from FPSE thinking I could do better. Botanical Heights (BH) was my next stop, right across Tower Grove Avenue from FPSE.

When I spend time in BH, both good and bad examples of development are on display. Parts 2 and 3 of this series will explore just that, from my personal perspective using my Spidey-senses with some colloquial opinions of people I’ve talked to.

The answer is never easy as to the benefits or ills of gentrification. Anyone who thinks it is strictly black and white or good or bad likely has an emotional or idealist take and has not considered the history and trajectory of a place.

Again, BH has and is under going active gentrification. But, is it bad? Is it good? This is what I hope to shed light on from my and others’ perspectives.

I recently went to BH to walk the streets and alleys to talk to folks living or working in the neighborhood. And if this sounds like an exotic journey, it is not, I live < 2 miles from here and have spent a decent amount of time here.

So, if gentrification in St. Louis is usually followed by the thud of hitting rock bottom or driving something so far into the ground that everyone leaves on their own. Then, any investment, anybody moving back in after rock bottom can be called urban pioneers, gentrifiers, etc. It is a St. Louis brand of doing business.

BH has a little bit of both, this hitting rock bottom via choking off and the full blown buy out or urban clearance, “we” are taking over method.

So BH it is! That’s our backdrop for this topic.

Let’s take a moment to consider the official boundaries and U.S. Census data for BH.

I will not be discussing the non-residential area north of Park Avenue. As you can see the residential area is quite small, but I think it tells the story better than any spot in town.

Now let’s look at some demographics and housing trends from 2000 and 2010 Census data.

The Census data showed staggering population loss from 2000-2010. Was this due to gentrification? I think yes, in part due to the new single family homes with large yards versus the many multi-family, densely built homes that the neighborhood was built for when we still had lots of people living here. The # of occupied houses decreased, indicating the transitional nature of the neighborhood in that time period; yet, the # of vacant properties decreased. White and Asian people started moving in with whopping numeric increases, black and Hispanic/Latino people out.

The neighborhood went from ~89% black in 2000 to 74% black in 2010. I suspect the numbers will continue to become closer to 50/50% by the 2020 count. This is based on just walking around and seeing who lives in both the suburban style homes and the older brick homes on each side of Thurman. For context, the city is ~50:50 black:white, so BH is likely becoming a neighborhood reflective of the overall demographic of St. Louis. But will it stay like that in the 2020 Census count?

BH is a tale of two neighborhoods. Thurman Avenue is the dividing line between two different kinds of gentrification.

Herein lies the perfect neighborhood to consider gentrification and urban clearance.

Part 2 will take on the section of BH east of Thurman, framing the negatives of gentrification.