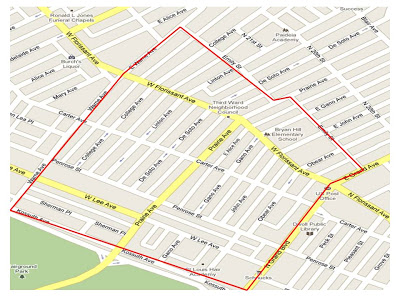

Fairground Park is a north St. Louis neighborhood bound by Emily Street to the north, Kossuth Avenue to the south, Warne Avenue to the west and Grand Boulevard to the east:

The 2000 census data counted 2,472 residents (down 33% from 1990's count) of whom 98% were black, 1% white. There were 1,216 housing units counted, 71% occupied (48%/52% owner/renter split). Another north city neighborhood that bled residents at an alarming rate from 1990-2000. A drive through this part of the city makes you understand why people are migrating to other areas. I would be surprised if the occupancy rate on housing is at 71% today, Things got worse in the 2010 census as another 27% up and left continuing the massive amounts of black flight from all black north city neighborhoods. This neighborhood is rough and I'd be lying if I didn't describe it as such.

Before I get started here, there are 2 excellent stories on Fairground(s) Park for which the neighborhood takes its name by Kate Boudreau from the UrbanSTL Website:

Postcards from the glory days of Fairground Park

It's hard to think about the massive losses we've experienced as a city over the years. It's hard to believe we let this happen. What a disposable society we are that allows this kind of architecture and history to fall by the wayside. Fairground Park is crumbling and is a tad threatening in more ways than one. This has been a volatile place when it comes to race relations in St. Louis going back to the 1940s. There was some major violence back in 1949 when the city ordered the desegregation of the swimming pools in the park. After a couple days of violence and blood shed, the city decided to go back to segregation. There's an excellent retelling of the story summarized on the Missouri History Museum website:

On June 21, 1949, a race riot took place when, for the first time, African Americans were permitted to enjoy the pool. The violence occurred against a background of inconsistency when public practice in St. Louis had not caught up with federal laws related to desegregation.

The Division of Parks and Recreation operated under a deliberately vague policy in relation to its facilities. While the Social Service Directory indicated that all facilities were open to all people, the Commissioner, Palmer B. Baumers, admitted that they were, in fact, restricted. When pushed about the issue, he said, “I inherited this. We just try to please everybody.”

In 1949 the city provided seven indoor swimming pools, four for whites and three for African Americans. The two outdoor pools in city parks were for whites only. The day before the pools were scheduled to open in 1949, a reporter from the long-defunct St. Louis Star-Times asked the city’s welfare director, John J. O'Toole, “whether Negroes could be allowed to swim in all the city’s public pools,” as “there was no law saying they couldn’t.” O’Toole replied: “If the colored people apply for admittance, my order is to admit them. I am not going to be a party to an unlawful gentleman’s agreement.” He used the phrase, gentleman’s agreement, to describe the tradition of segregation that the commissioner seemed to endorse.

When the pool opened on June 21, 1949 and African-Americans and whites were allowed to swim. A crowd of white youth congrated at the pool gates and were getting rowdy. The police escorted the black kids home safely. Nothing happened there, but troubled ensued in the evening hours.

It took more than 150 police officers until the early morning hours to dispel the crowd of 5,000. When the streets finally cleared, ten African Americans and five whites had been hospitalized.

The next day Mayor Joseph M. Darst ordered both of the outdoor pools closed and announced that the city would return to its practice of segregation. While admitting that O’Toole was “on sound legal ground” in integrating the pools, the Major argued that segregation was right for St. Louis:

. . . there has existed for many years in St. Louis a community policy with respect to public swimming pools, voluntarily complied with by both white and colored citizens. Our white citizens have customarily used the pools conveniently located to them, while the colored citizens have patronized the pools in their neighborhoods.

This practice has worked well. St. Louis has become noted for its tolerance and its progress in the field of amicable race relations. In the months that followed, the newly formed St. Louis Council on Human Relations commissioned a report, “The Fairgrounds Park Incident,” which was prepared by George Schermer, director of the mayor’s inter-racial committee in Detroit. While the ostensible purpose of the study was to find solutions and not to lay blame, the newspaper article that describes its release makes other implications: “Responsibility for the racial disturbance at Fairgrounds Park June 21 must be shared by many people—public officials, civic, religious, business and labor leaders—and by Missouri’s segregated school system, an investigator, George Schermer, said today.” Schermer cited “the failure of community leadership to prepare St. Louisans for the adjustments which changing population, economic, and social conditions are forcing upon the community.” The report concluded with 22 recommendations; foremost among them was the statement that “the exclusion of any citizen from municipally-operated public facilities because of his race is a violation of that person’s civil rights and contrary to law.” Schermer also recommended a city-wide educational program to “cultivate respect for individual civil rights and an expansion in the public schools of education in democratic human relations. . . .”

The next year U.S. District Judge Rubey M. Hulen ordered the City of St. Louis to open all city-owned and operated outdoor swimming pools to all citizens, and Major Darst urged the public to comply:

The federal court has construed the Constitution of the United Sates to require that all persons regardless of race shall be allowed to use our public outdoor pools. Our military forces are fighting today 5,000 miles from our shores to establish and protect the doctrine of the “dignity of man.” Our country is girding itself for a wartime economy. Sacrifice is the order of the day.

Under such circumstances, we cannot afford the luxury of prejudice. We must not allow disrespect for the Constitution and the courts. With these grudging words, the pool at Fairground Park was opened to all, and the story of the riot seemed to disappear from local memory. From the start, there was a tendency to minimize. Schermer noted that some city officials saw an injustice in calling the episode a “race riot,” as it involved only a “small number of persons of the ‘hoodlum’ type.” Others, like Eddie Silva, writing in the Riverfront Times in 2002, see an example of the cultivated complacency that allows St. Louis to ignore a persistent history of racism. In acknowledging this chapter in the history of Fairground Park, we can profit from the conclusions in Schermer’s little-known report. It is still a good idea to engage in citywide dialogue that cultivates respect for human rights.

Racial tension is not a problem that plagues current day Fairground Park as the citizenry is nearly 100% African American....zero diversity. Unfortunately, this appears to be a forgotten place for almost all city services excluding the police who had a strong presence during my time here today. Buildings are burned out, crumbling, collapsing and rarely boarded up. There is trash lining the streets and roads. There is rampant dumping and other bad behavior on all levels.

When the sidewalks are covered in ice and snow, people are walking in the streets to get from here to there. So, the level of racial and other commentary was especially thick today and nice and close to my car window so I got a good earful. When one of the neighbors was questioning my existence in his neighborhood, I asked if he knew what the name of the neighborhood was and he said "yeah, crime neighborhood". I'll take his word for it, as there is evidence of all kinds of trouble to be found here. This is one of the part of town that I would categorize as unwelcoming and/or dangerous. That's not to say the police aren't working hard here, they were all over the place and tracked me for awhile until they found out I was taking photos and not looking for a hookup. I am always appreciative the police presence in some of the tougher parts of town.

Here's some sights from Fairground Park today:

Even the more contemporary infill of the last 20 or 30 years has not righted the ship:

I love the view of the 2 water stands in College Hill and the church steeple providing a great skyline on N. Grand just south of Florissant Ave:

While sights along Grand are largely suburban styled strip malls and a large supermarket, there are some interesting buildings including the former North St. Louis Trust Co:

Some impressive churches and schools still exist:

Check out the barbed wire on the top of this former apartment complex.

And some of the cooler signs and businesses past and present in the neighb:

Fairground Parks is a reminder that much of our city is completely uncared for and still in a state of decline. The people in charge and others that led to the current day state have collectively thrown their hands in the air and said, what can you do?