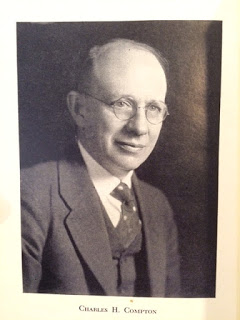

The Compton Library at 1624 Locust Street, accessible by appointment only, was named in honor of Charles Herrick Compton (1880-1966).

A staunch advocate for the library system in St. Louis, and public libraries in general, Compton was employed by the St. Louis Public Library from 1921-1950. He became the Director in 1938 and held that position until 1950 when he retired. The Compton Library was built in 1957.

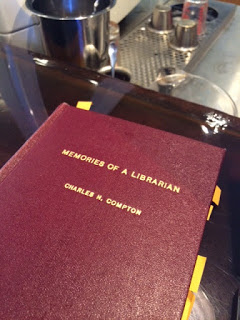

Online information about Compton's life is fairly limited, so it felt like a little old fashioned research seemed appropriate. Luckily, Compton published a detailed record of his early life and professional career called "Memories of a Librarian" which was published in 1954 by the St. Louis Public Library.

A book about a librarian, I know what some might be thinking...quiet work spaces, books, Dewey Decimal Systems, etc...paint drying. Yet, the recount of his career pulled me in from the start. His life and stories paralleled America's best of times and worst of times. His career coincided with America's involvement in World War I, the Roaring 1920's and the Great Depression of the 1930's where in one of his speeches to the American Library Association in Denver in 1935 he said:

"As I look on the past twenty years of war, boom, depression, they are painful years. As I look on the world today, it is all too much a ruthless and a senseless world. As I look toward the years to come, there is a foreboding, but my faith in democracy is unweakened, my belief in libraries as essential in a democracy is unshaken. Libraries will be a part in making of the new and better world which we all desire."

Compton chased that desire and spirit throughout his career and his attention to detail and writing style lend insight into his quirkiness as a staunch book lover. He once said of his profession:

"We librarians are a chosen people, a peculiar people in our own eyes and perhaps peculiar in the eyes of others."

Maybe so, but Compton's successes and accomplishments transcended any bookworm idiosyncrasies or self-imposed limitations; this man took public libraries to a new level in America and St. Louis was lucky to have him.

So the purpose of this post is to highlight his time in St. Louis and the suburbs to the west of the city as well as some of his key accomplishments.

But first a little background on his early life and lead up to his move to St. Louis.

Compton was born in 1880 in Palmyra, Nebraska, and later moved to Lincoln, Nebraska where he attended a two year preparatory school run by the University of Nebraska where you could finish your four year high school degree in two years.

He went on to attend the University of Nebraska, graduating in June, 1901.

After graduating and working a number of jobs that took him from Minneapolis to Billings, Montana and eventually back to Lincoln, he soon decided, somewhat by chance, that he wanted to be a librarian, inspired by his sister, who was an assistant at the University of Nebraska Library.

He followed his heart and in October, 1905 took a train to Albany, New York where he enrolled in the New York State Library School. According to Compton this was "when life began for me." During his schooling, he became the librarian of the Albany Y.M.C.A. in 1906. He graduated with his degree in June, 1908.

A few months later, he landed a job as librarian at the University of North Dakota and moved to Grand Forks, eventually married in 1908 and started a family in 1910 with the birth of his first son. The library was one of the 2,509 Carnegie libraries built between 1883 and 1929 throughout the United States.

After working for the University of North Dakota for a year and a half, he accepted a reference librarian position with the Seattle Public Library. Here he made a name for himself by focusing on fund raising and publicity for the library system in the Emerald City. As a result of his efforts and diligence, patronage rose 150%, the book collection nearly quadrupled and the periodicals doubled. Seattle is where Compton blossomed professionally. He started receiving invitations to more and more library associations and speaking engagements at regional conferences. His second son was born in 1914 and they bought their first house.

In 1918, Compton was given leave from the Seattle Library to lead an effort by the Library War Service in Washington D.C., who had requested the American Library Association set up a program to provide reading materials to servicemen both domestic and abroad during and immediately following WWI.

Compton met many influential and talented people in his field during his tenure in the Libary War Service in D.C. He managed a budget of $70,000 per month and was buying an average of 2,500 books per day to establish the library for servicemen. He worked hard, seven days a week and his mission was an overwhelming success. Nearly 3.4M books were shipped to outpost camps, hospitals and bases throughout Europe and the United States. His service and the war came to a close and he returned to Seattle in 1918. In six months he assumed the head librarian position at the Seattle Library.

This service during WWI inspired Compton to take what he had learned and apply it to the homeland as well...for the good of the public. He became part of the "Books for Everyone Campaign" and moved to New York City traveling to and from NYC and Chicago to help lead this effort which espoused the tenet that "good books made good citizens". He amassed a staff of up to 30 employees who were "banging away at the campaign with might and main." The group set out to raise $2M to fund the campaign to distribute books to the public libaries across the country, but the efforts failed to raise their target and the group eventually disbanded. Compton and his family did not like NYC or Chicago life and were happy to return to Seattle in 1920.

In the Spring of 1921, Charles H. Compton was offered the position of assistant librarian of the St. Louis Public Library and by June he was working in St. Louis. He was connected with the head librarian at Washington University who took him under his wing and put him up in a room in his home on Cates Avenue in what is now called the city's West End Neighborhood. When he moved his family to the area, they rented a house in the small town of Kirkwood, MO (pop. 4,500) ~ten miles from St. Louis. When settled they looked for their first house, and chose another small town ~eight miles from St. Louis called Webster Groves, MO (pop. 9,500) in 1922. The home is no longer standing as it was demolished for Interstate 44 construction just south of Webster University's main campus.

The family adapted to life in the suburbs of St. Louis quite well. Like most, they became infatuated with baseball and attended many games at Sportsman's Park watching Babe Ruth play against the Browns, but the Cardinals were their favorite team. The Compton's were accepted into St. Louis Society with open arms led by Charles current love for Mark Twain and Carl Sandburg which carried over well with the men's clubs he was part of that included the Dean of Washington University and former St. Louis Browns and Cardinals great Branch Rickey who eventually went on to sign Jackie Robinson to the Brooklyn Dodgers thus breaking the color barrier in the Major Leagues.

He had a hand in establishing the Webster Grove Public Library on a tax supported basis in 1927 when he served on that library's board until 1931 when he resigned to move to St. Louis after his kids graduated high school in Webster Groves and went to Washington University. They moved to an apartment at 5888 Cabanne Avenue in the West End Neighborhood.

His respect in the National library community was growing and he became President of the American Library Association in 1934 amid the Great Depression where he was tasked with resetting the charter for the Association during the "perilous and trying times" where he rallied librarians to emerge from the "cheerless years" and lead libraries to a brighter day ahead.

Compton's work and inspiration seemed to draw from his American experience of the Great War and the Roaring 20s and the Great Depression. His no-quit spirit during the Depression led him back to Washington D.C. where he led ALA discussions with the Agricultural Deptartment to collaborate on gaining access to public libraries in America's most rural parts. This was a most noble cause, but an increasingly uphill battle when the Treasury was shrinking. This never came to be, but he continued his pursuits and represented St. Louis well.

Once again faced with the precipice of the changing times, Compton was assigned as a delegate to the International Library of Congress which took him to a conference in Europe where he was hosted by a fellow librarian of German descent. They spoke of Adolf Hitler's rise to power in Germany acknowledging Hitler's successful management of banking, currency and general economic conditions while lamenting his hatred for Hitler's views toward Jews.

Throughout his expanding endeavors, he was successful in raising funds and expanding the library system in St. Louis. He was a wonderful advocate and diplomat for free public libraries and books in general.

In 1938, Compton was assigned head librarian of the St. Louis Public Library. And, in 1950 at the age of 70, he chose to retire. Reflecting on that time in his life he said: "I dislike the word gerontology. The very sound of the word is disagreeable. How to grow old gracefully certainly deserves a more pleasing designation."

Beloved by his peers and associates, a huge party was thrown for him in 1950 where hundreds turned out ranging from library staff to media members to national and international friends and colleagues attended. At this celebration he stated: "I feel that we all should be tremendously proud of our profession. Many of us became librarians by what seemed mere chance. Certainly that was true in my own case. Librarians almost universally are happy in their work and would not change to other professions. Librarians have enthusiasm for the work they are doing. Life without enthusiasm is not worth living."

His praises were sung by dignitaries ranging from St. Louis Mayor Joseph M. Darst to First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt. He was lauded for bringing the St. Louis Public Schools and the Public Libraries together through collaborations.

Today, where all printed materials are being scanned, digitized and uploaded for full global access via the web/cloud, it is uncertain as to what the future holds for books and libraries in general. One thing for certain is that in Charles Compton's 29 years with the St. Louis Public Library, he was able to take public libraries to a new level in our fair city.

Charles H. Compton lived to the age of 85. He died on March 17, 1966.